Gurdjieff International Review

Further Episodes with Gurdjieff

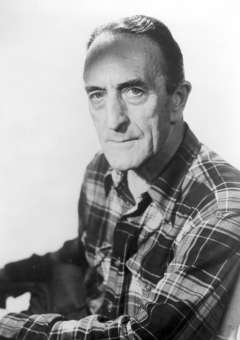

Related by Edwin Wolfe

After some formal training, he played the lead roles in two silent films, then succeeded in gaining fairly steady employment both on the Broadway stage, and in traveling stock companies. Although he enjoyed acting, shortly before the United States entered World War I he enrolled as a student in medical school, an indication that he wanted something more from life. However, after the war broke out he entered the army as an ambulance driver and, following the armistice, felt he was too old to ask his father to support him while he continued his medical studies, so he returned to acting. He made a modest living, traveled about the U.S. a great deal, drank quite a bit, was addicted to reading mystery novels, and often played cards with fellow cast members for whole days. In his own words, he “didn’t know what to do with himself.”

In 1927 he saw a notice that an old acquaintance of his, a student of psychology named C. Daly King, whom he had never taken very seriously and whom he mentally referred to by his nickname, “Pudge,” was going to give a talk on “psychology” at a bookstore. Mr. Wolfe went to the talk expecting to be entertained at King’s expense, though with his innate tact he would never have openly offended King. However, unbeknownst to Mr. Wolfe, King had come into the Work in 1924 and was a member of A. R. Orage’s group. His talk, which consisted of several of Gurdjieff’s basic ideas, made a tremendous impression on Mr. Wolfe. He told members of his group, in about 1980, that when Daly King said that our various functions such as thought, feeling, movement and sensation were controlled by separate brains, or “centers,” “I rose straight up to the ceiling—and haven’t come down yet.”

Mr. Wolfe immediately realized he had come upon something of the utmost importance that he had long been vaguely aware was missing from his life, that a dream he had never dared to dream had come true. Now that he knew “what to do with himself,” he became a very conscientious student, and soon went to the Prieure in France to work with Gurdjieff.

Mr. Wolfe’s good luck continued. While at the Prieure he met Dorothy Hunt, the love of his life, whom he married. In 1933 he answered a call for directors, and entered radio, which was becoming immensely popular, as an actor and director of soap operas. He was very successful and prospered.

Between the ages of ten to thirteen I used to come home from school, which was nearby, to have lunch. While I ate, I listened to a few soap operas. The best one by far was called “Ma Perkins.” “Ma” was a mature woman who often made shrewd and interesting remarks. She had a knack for seeing through people’s pretenses and for discerning offbeat significance in various situations. There was also a character on the program who always refused to inner-consider anyone. I still remember his name: Roger Dineen.

Several times, I remarked to myself that I had learned more about life from listening to “Ma Perkins” for fifteen minutes than I had the entire day at school. The program always ended with the announcer saying, “Ma Perkins was directed by Ed Wolfe.” Occasionally I would repeat those words to myself, sing-song style, a few times. Could it have been a sign, a portent, that nearly twenty years later the door of an apartment in New York City would open, and that behind that door, waiting to admit me to the Work, was Edwin Wolfe, once the director of “Ma Perkins?”

After Gurdjieff’s death Mr. Wolfe became a group leader, and was a founding trustee of the New York Foundation. His intelligence was so obvious that when a neighbor of his, the writer Rex Stout, launched a series of “whodunit” novels he named his brilliant protagonist-detective “Nero Wolfe.” However, the quality of his that we, his students, found even more impressive was that in every encounter or exchange with him we were made to feel that his paramount interest was our well-being. Mr. Wolfe told us that at times he had to struggle against the impulse to let the respect we gave him be taken by his ego. Clearly, we all felt that he succeeded admirably in this struggle. During his last years he exclaimed several times, “Gurdjieff saved my life!”

As he lay dying of congestive heart failure in 1983, he exhorted the students who were attending to him, when they became agitated, to “Take your time! Take your time!” So he continued to teach the Work, and to put his students’ welfare before his own up to his last breaths.

In 1974 the Far West Press brought out a slim volume—recently reissued—which Mr. Wolfe had written, entitled Episodes With Gurdjieff.1 I was told he was planning a sequel, but it never materialized. However, he did relate a number of further episodes with Gurdjieff during group meetings and work days at his home which, to the best of my knowledge, have never been committed to paper. I have recorded them here in the hope that they will be of some interest and value.

I

In Paris there was a restaurant Gurdjieff often went to because he liked the crawfish they served there, which was called ecrevisse. One evening, during the period in which he was writing All and Everything, Gurdjieff and some of his people went there for dinner. However, on this occasion Gurdjieff did not order ecrevisse as he invariably did. Someone in the party made a remark about this. Gurdjieff acknowledged the remark and went on to say, “I did not write as much as I should have today, so tonight I will not have ecrevisse. Tonight I will eat something else.”

II

While engaged in a conversation with some of his people about the English language, Gurdjieff said that there was a certain word that had to exist in it. Some of those present, among whom were men and women whose native language was English and who were, moreover, well-educated, expressed their doubts about this, but Gurdjieff insisted. The conversation passed on to other subjects, but as soon as they left the gathering Mr. and Mrs. Wolfe went directly to the American consulate and consulted the unabridged English dictionary. They found the word almost immediately. It was “antipathic.”

III

One day, at the Prieure, Mr. Wolfe was with Gurdjieff and some of his people when a group of men came up to them and told them there was a man in one of the buildings there who had a question, and that if he couldn’t get an answer to this question he was going to kill himself. With everyone following him, Gurdjieff immediately went to this man. Mr. Wolfe said that the moment his eyes fell on him he could tell he was indeed in a very bad way. Gurdjieff walked up to this man and faced him squarely. He did not say a word but seemed to Mr. Wolfe to confront the man with his full presence, his full force. They stood face-to-face that way for some time.

There was a table in the room on which rested some oranges. Not taking his eyes off the man, Gurdjieff gingerly moved to the table and picked up two oranges. He retraced his steps and held out the oranges to the man, one in each hand. Slowly, silently, the man took both. Soon Mr. Wolfe noted that the man underwent certain changes. His body relaxed. The acute tension dropped from his face, and it regained its normal skin tone. His breathing grew more regular and, after a while, he became his normal self again.

IV

At a meeting, Gurdjieff took special note of a particular man. Mr. Wolfe could see that the man was very dejected, very depressed. Gurdjieff engaged the man in conversation, quickly drawing out of him what his chief interests were. He asked the man for his opinions on some of the finer points of these subjects, then complimented him on his insights. As the conversation progressed, the man visibly brightened; by the time he was ready to leave he was positively glowing.

After he was gone, Gurdjieff turned to those who remained and said, “He not feel good. I take him under my wing. I warm him a little.”

V

During a conversation, the subject of cremation came up. Gurdjieff advised against it. “It destroys something,” he said.

VI

In an exchange about Beelzebub’s Tales and what lays hidden in the book, Gurdjieff said,

“I bury dog.”

“You buried the bone,” someone ‘corrected’ him.

“No,” said Gurdjieff, “I bury whole dog.”

VII

Preparing to embark on one of his transatlantic trips, Gurdjieff had a large number of watermelons brought on board the ship. When the ship’s officials saw them they told Gurdjieff that they would have to be removed. It was against regulations. Gurdjieff kept insisting that they would have to make an exception in this case “These special melons,” he repeated many times, playing an elderly eccentric. Convinced by his role-playing, the officials decided that the ‘poor old man’ was obviously a little touched, so they allowed him to sail with the melons.

VIII

On another occasion Mr. Wolfe heard Gurdjieff tell someone not to attempt to defend his (or her) spouse against a reprimand from him. Mr. Wolfe summed up what he felt was Gurdjieff’s lesson here: “In the Work we are all brothers and sisters. But in the Work there are no husbands and wives.”

IX

A man, who was not a pupil, asked Gurdjieff what he was trying to do. “I try to make human beings,” Gurdjieff replied.

X

After Mrs. Dorothy Wolfe’s father died, she mourned for a very long time. She simply could not get over her grief. Thinking that perhaps there was something not quite right about this, she asked Gurdjieff what to do. He told her to select a prayer that was special for her and recite it regularly, with the intention of sending help to her father. He said it would reach him for twelve months; after that he would be beyond reach. Mrs. Wolfe took his advice and reported to her husband that it helped a great deal.

XI

Mr. Wolfe was once present when Gurdjieff was chatting with several students who obviously idolized him After they left, Gurdjieff shook his head regretfully and said to Mr. Wolfe, “These people think I not use water closet.”

~ • ~

1 Edwin Wolfe, Episodes with Gurdjieff, San Francisco: Far West Press, 1974, 38p.

| Copyright © 2003 Gurdjieff Electronic Publishing Featured: Spring 2003 Issue, Vol. VI (1) Revision: April 1, 2003 |