Gurdjieff International Review

Tradition and Transmission in the Music of Gurdjieff

Laurence Rosenthal

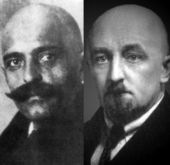

It is just possible that in no art, with the exception perhaps of the dance, is the verbal method of instruction or transmission so inadequate, written or even spoken, as in music. In the instance of the music of Gurdjieff, so intimately related to certain facets of tradition, and yet oddly separate from other aspects of it, this difficulty of transmission is considerably augmented. One can attribute the difficulty to a number of causes, but primarily it is that the inner import of this music far transcends its compositional features and its apparent ethnic references. Then there is the unmistakable particularity of Gurdjieff’s musical gait, his personal accent, his not-quite-conventional manner of moving through a sonic landscape. Thomas de Hartmann’s sensitive, elegant realizations of Gurdjieff’s germinal musical thoughts often clothe their limbs in sophisticated European dress. But the origin of the inspiration is never in doubt. De Hartmann is always faithful to the uniqueness of the master’s tonal speech, and even his refined harmonies do not obscure or mask the idiosyncratic flow of Gurdjieff’s melodic impulses.

The remarkable results of this extraordinary collaboration are authentically revealed in the magisterial pianism of de Hartmann’s recordings;[1] we are hearing Gurdjieff’s voice. And although we have, captured on tape, Gurdjieff’s own harmonium improvisations as a living document, it can surely be said that de Hartmann single-handedly created the tradition of the performance of this body of music. (Even in the excellent recordings by Jeanne de Salzmann and Carol Robinson, one hears the persuasive influence of de Hartmann’s interpretations, with which they were both well acquainted.) Though de Hartmann has spoken and written movingly about Gurdjieff’s view of music as a higher force and as an embodiment of religious feeling, it is de Hartmann’s own performances of the music that are, for those who study these pieces, the unimpeachable guide. So that finally it could be said that rather than an oral tradition, what remains to us is an aural tradition.

However, this aural tradition is obviously only the point of departure in regard to transmission to a pianist attempting these works. Imitating the surface of the model is a time-honored practice; great artists have almost always begun that way. But clearly if the pupil does not go beyond copying the external gesture, its essence will completely escape him. It must be sought and rediscovered with every performance, with every hearing. And what is this essence?

It is perhaps here that the investigation of Gurdjieff’s music begins to diverge from normal musical study, even of great masterworks by rightfully celebrated composers. Gurdjieff was in no way a professional musician. Although the numerous references in his writings to the extraordinary properties of music and its uncanny capacity to influence the human body and psyche attest to the importance he attached to this art, his specific purpose in creating a substantial repertoire of piano pieces remains nevertheless undeclared by him. In view of the magnitude and the intensity of this enterprise, one comes unavoidably to ponder his motive and to search, as it were, “behind the notes.” After all, the printed scores are, as with all music, merely an architect’s blueprint—perhaps even less than that: a vastly imperfect and limited set of symbolic instructions. They are, of course, essential, but they are at best approximate and incomplete, and they are mute. They are waiting to be infused with the breath of life, to be made meaningful in the light of understanding, to be transformed by the musician into sounding melody, harmony, rhythm. Music is alive only when vibrating in the atmosphere.

And it is precisely these vibrations to which player and listener must become sensitive. This is in fact the moment of transmission. And suddenly one is engulfed by myriad questions. What is coming through the air? What am I receiving? What do the tones convey? What is this music about? What truths does it express? What in fact is it saying? Why does it seem to evoke the poignancy of the life of Man, the forces to which he is subject, the enigma of his destiny? And how has all of this been encapsulated in sound? How transmitted?

We are back to the inadequacy of words. Music is its own language, and its mysterious action, its sympathetic resonance within us, cannot be described, only experienced. Furthermore, the transmission must happen anew with each performance, with each audition.

One can study Gurdjieff’s monumental corpus of ideas. One can practice his miraculous Movements. But the reception of his music, especially the deepest works, takes place in an unknown interior realm. It may depend on a certain preparation, perhaps somewhat unlike what is usual for other music. It may require a willingness to abandon certain associations, certain regions of one’s conditioning; to bring the body to a relaxed readiness; to approach a state of silence, immobility, and emptiness. It is an inner work in which another, perhaps subtler, intelligence is engaged. These vibrations, these tones, have the capacity to penetrate, to permeate, to open the organism. They can speak directly to the educated heart. Or perhaps, in fact, they serve to educate that very heart.

~ • ~

Composer and pianist Laurence Rosenthal has studied the Gurdjieff / de Hartmann music for many years.

| Copyright © 2012 Gurdjieff Electronic Publishing Featured: Spring 2012 Issue, Vol. XI (1) Revision: April 1, 2012 |